-40%

The Third Battle Of Winchester VA Civil War Dug Relic Dropped .52 Sharps Bullet

$ 10.55

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

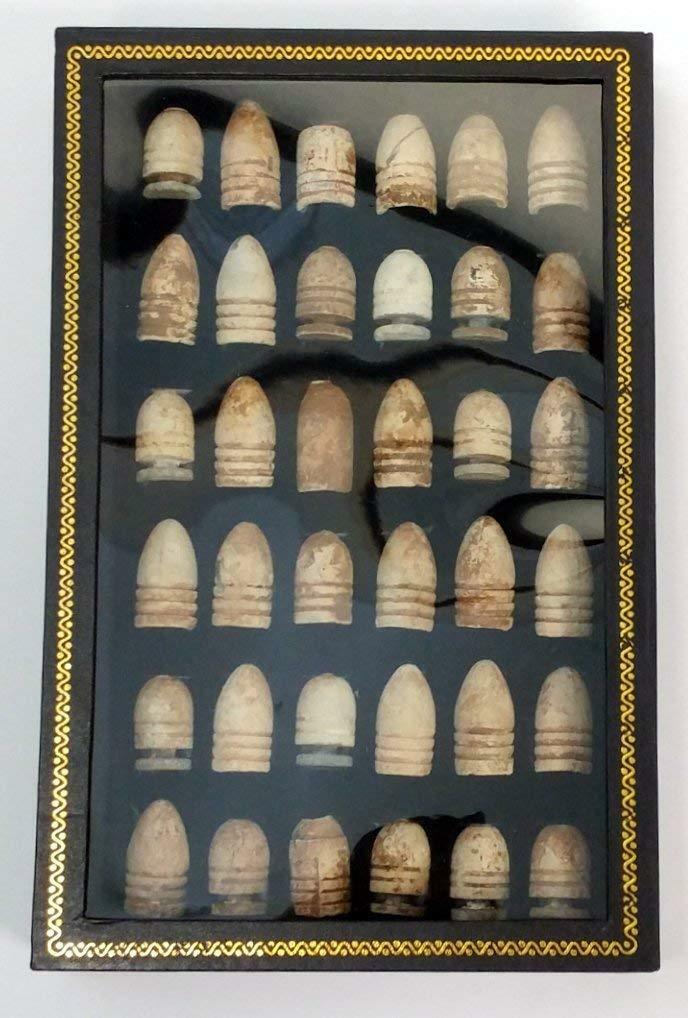

We are working as partners in conjunction with Gettysburg Relics to offer some very nice American Civil War relics for sale.THE (THIRD) BATTLE WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA - THE WILLIAM REGER COLLECTION - A very nice Dropped .52 caliber hole-base Sharps Bullet

This very nice dropped hole-base .52 caliber Sharps Bullet, which has great provenance from the Battlefield of Winchester in Virginia (likely from the Third Battle of Winchester, but possibly also lost at another time or in the Second Battle of Winchester. The First battle was on the West side of town and an overwhelming number of the relics were recovered from the site of the Third Battle of Winchester which was north east of the town of Winchester.

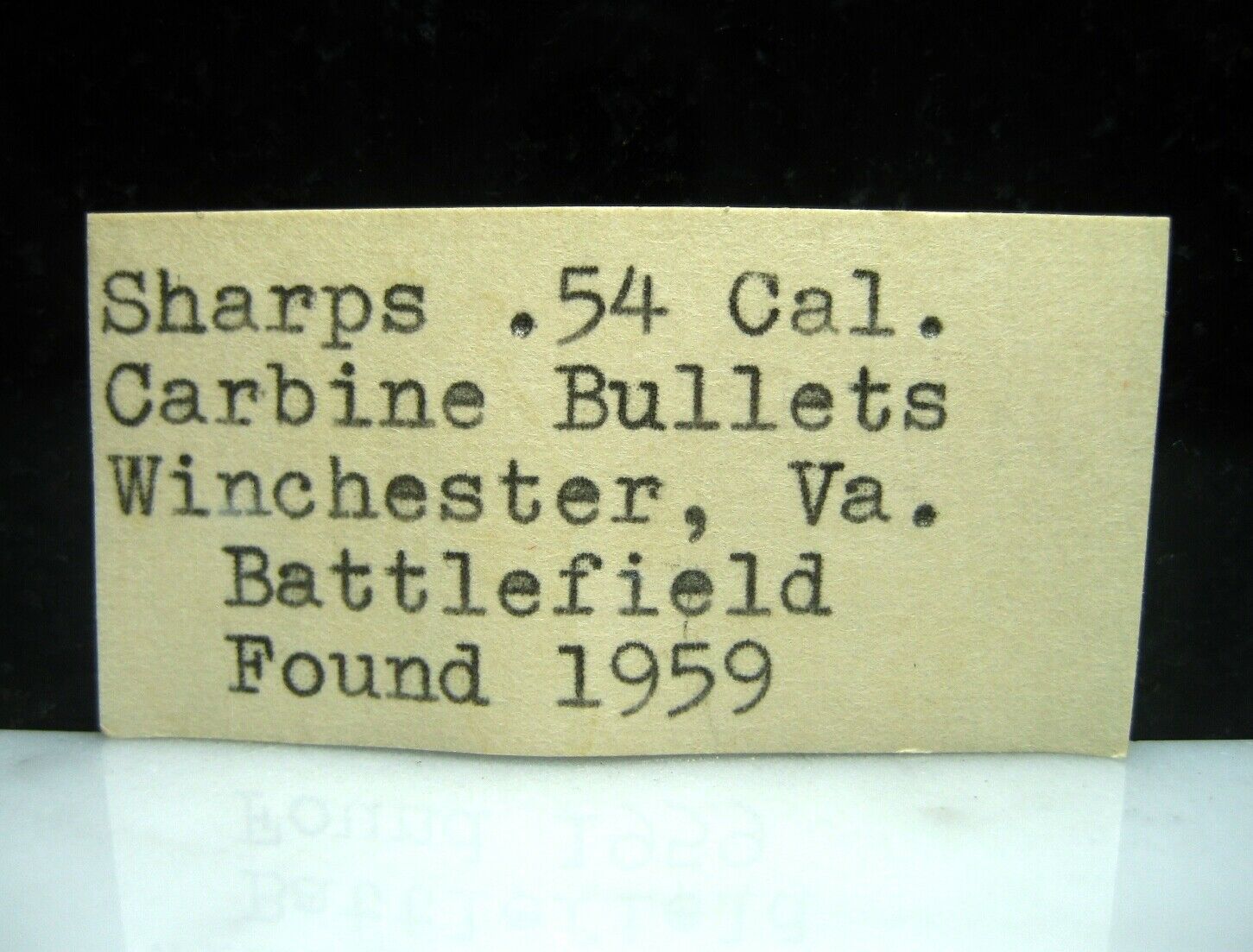

This relic was found by William Reger at the Winchester Battlefield in Virginia. This relic was in a large Pennsylvania collection of carefully identified relics that were recovered in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Reger included his own type-writer typed tags with the groupings of artifacts, and in this case, the tag in not included, as it was the only tag for the grouping, however, a copy of the tag, as well as a

provenance letter, will be included.

Military Occupation of Winchester, Virginia

While local historians boast that Winchester changed hands more than seventy times during the war, estimations of full-fledged occupations by either army range from eleven to thirteen. Wartime diaries suggest that Winchester was under Confederate authority for 39 percent of the war, occupied by Union armies for 41 percent of the war, and between the lines for 20 percent of the war. As a result of continued frustration in the Shenandoah Valley and evolving military policy, each successive Union occupation resulted in harsher measures toward civilians. Initially individuals were hassled and homesteads plundered. In the spring of 1862, Union general Nathaniel P. Banks attempted to placate Winchester’s population. Union general Robert H. Milroy, however, admitted he felt “a strong disposition to play the tyrent among these traitors,” embittering residents with his harsh policies throughout the first half of 1863. He required citizens to take oaths pledging their allegiance to the United States. If they refused, soldiers would quarter their homes. Milroy also permitted Union troops to obliterate Winchester, refusing to interfere when they razed every unoccupied house in town. Although Union general Philip H. Sheridan has an infamous reputation in the Shenandoah Valley, his occupation of Winchester in the autumn of 1864 brought some much-needed stability to the town.

Winchester residents quickly learned that the presence of either army had unpleasant consequences. In the summer of 1861, as Confederate troops inundated the town, one resident characterized Winchester as “a smelly dirty place.” Another noted that “15,000 Troops are around and about us. Nothing but soldiers—soldiers.” Diseases ran rampant, with approximately 2,000 soldiers sick with measles and mumps being housed in private dwellings. Most periods of Confederate control resulted from major battles, and on such occasions wounded soldiers overwhelmed the town. Residents estimated that between 3,000 and 5,000 wounded soldiers recuperated in Winchester after the Battle of Antietam in the autumn of 1862. “Every house is a hospital,” a resident observed at the time.

Inhabitants of occupied Winchester faced increasing economic hardship. By the end of 1861 inflation was rampant; salt that sold for a sack in August cost by December. The mid-October 1863 price of flour was per barrel. By November 1864, flour was for three barrels ( in greenbacks, rather than in hyper-inflated Confederate currency). One resident recalled, “People used to have a basket to carry their money to market in but it bought so little they could carry the provisions home in their pocketbooks.” Union occupations magnified this hardship by requiring buyers to take an oath of allegiance to the United States, which many residents refused to do. Winchester’s proximity to large armies quickly took its toll; in July 1863 Robert E. Lee wrote to his wife, “Poor Winchester has been terribly devastated, & the inhabitants plundered of all they possessed.”

Union occupations also contributed to the destruction of slavery in Winchester. Many slaves took advantage of Union military occupation to escape bondage, and even those who remained enjoyed increased autonomy when Union forces were present. Refugee slaves from the countryside entered Winchester in droves after the entrance of the Union army. One month after the first Union occupation, diarist Mary G. Lee noted that “[t]he freedom of the servants is one of the most irritating circumstances” of the Union military presence. In April 1864 a black Union regiment came to Winchester on a recruiting mission; while some men joined, the mission was largely unsuccessful. When Confederates swiftly returned to Winchester in 1862, 1863, and 1864, they captured many local slaves and returned them to their owners.

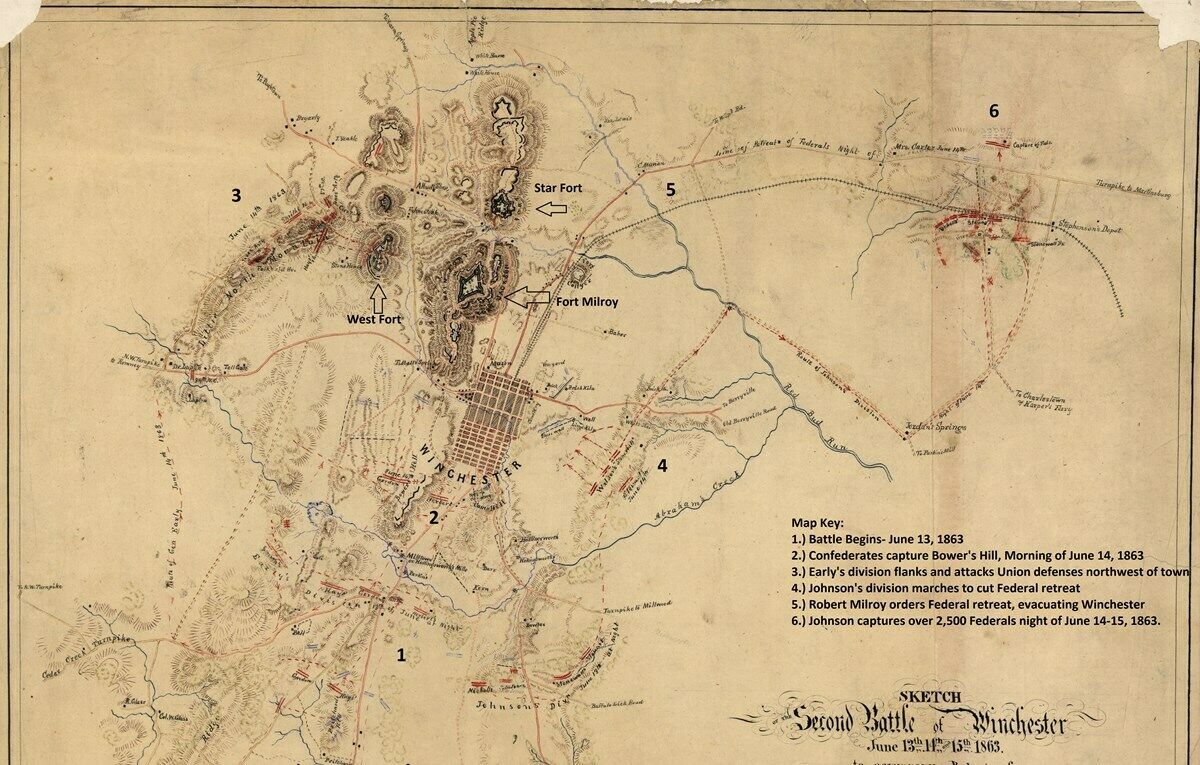

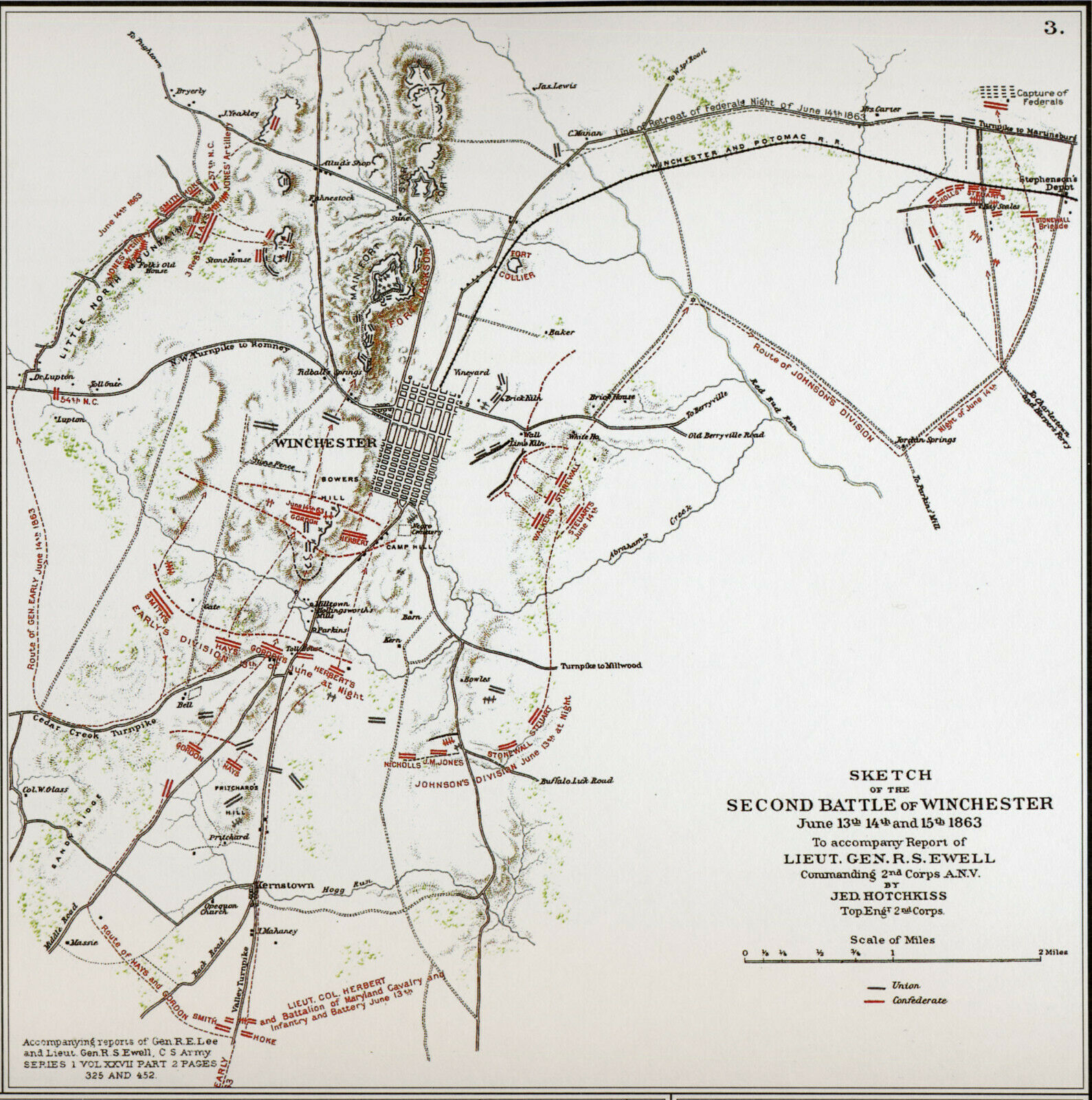

The battle became a rout. Although some Federal troops, including Colonel J. Warren Keifer and many of his 110th Ohio troops escaped, many other Union officers and soldiers surrendered. Harrowing tales of Union escapes abounded as troops fled not only to Harpers Ferry, but northwest toward Hancock, Maryland, and on to Pennsylvania. The desperate and confused Union commander, Gen. Robert Milroy, avoided capture by fleeing through fields toward Harpers Ferry. Along the way, he was heard to say, “Men, save yourselves!” and “Every man fight your way through to Harpers Ferry.”

Although casualty estimates vary, the jubilant Confederates had suffered only about 300 casualties at Second Winchester, while the Federals lost approximately 4,400 including close to 4,000 prisoners. Whatever the exact numbers, it was an impressive Rebel victory. Gen. Ewell made the right tactical moves to force Milroy out of Winchester and then rout the escaping Federals. The discredited Milroy was relieved and never held a field command again. For the people of Winchester, it was a time to celebrate the expulsion of Milroy’s occupation force. The citizens’ happiness was short-lived, however, when many of the Confederates returned in agony three weeks later after their bloody defeat at Gettysburg.

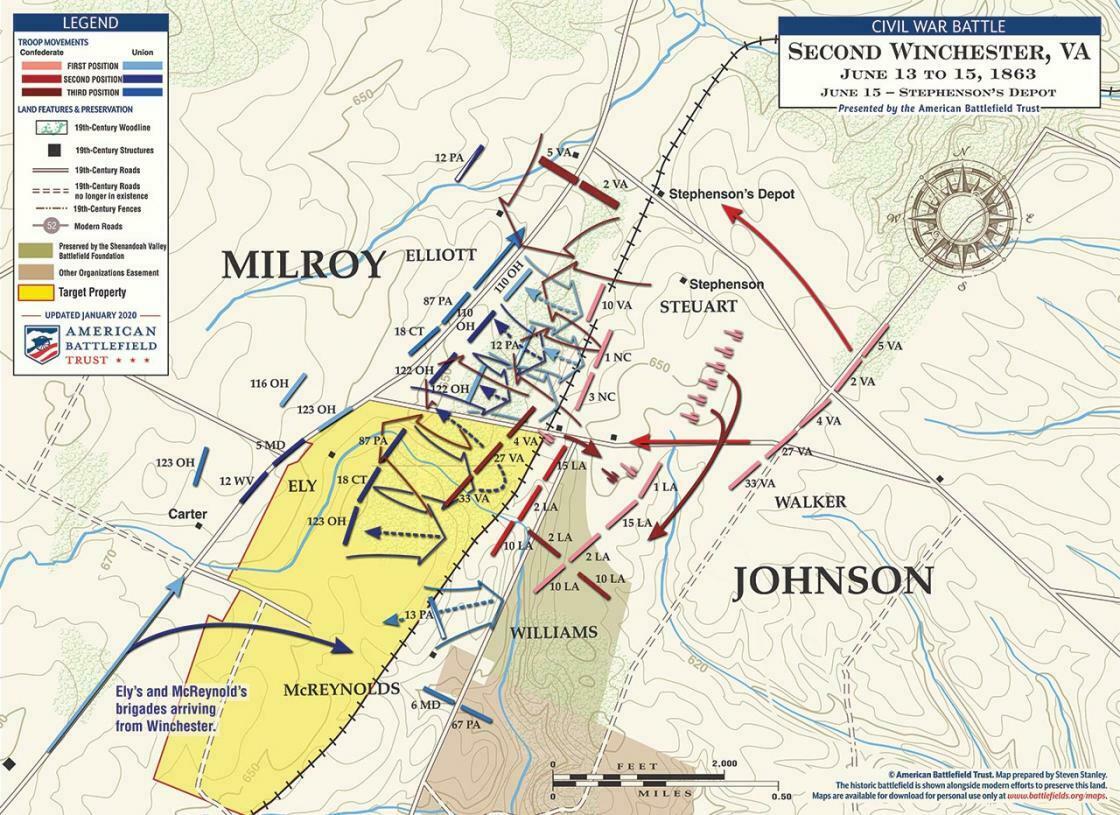

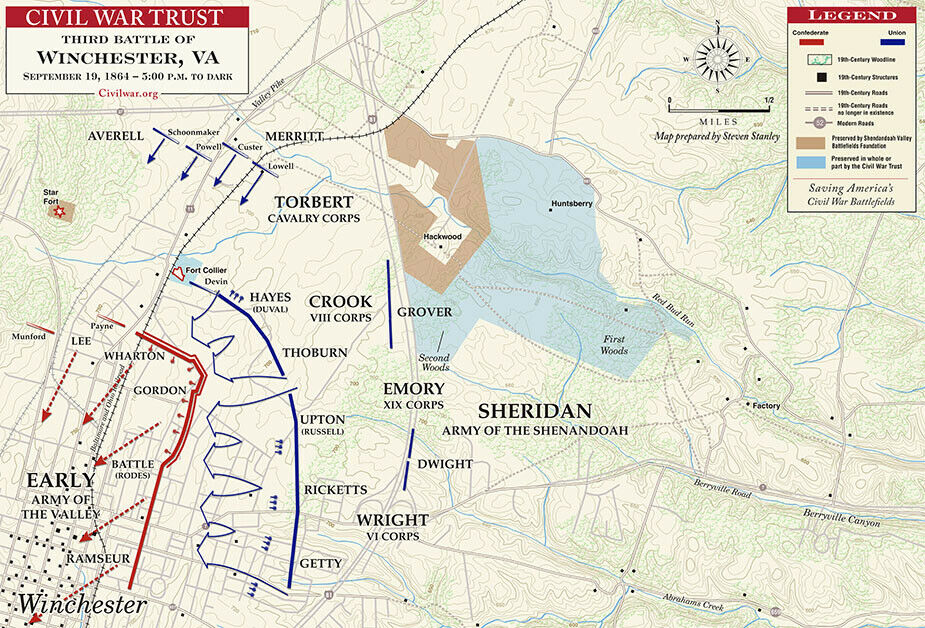

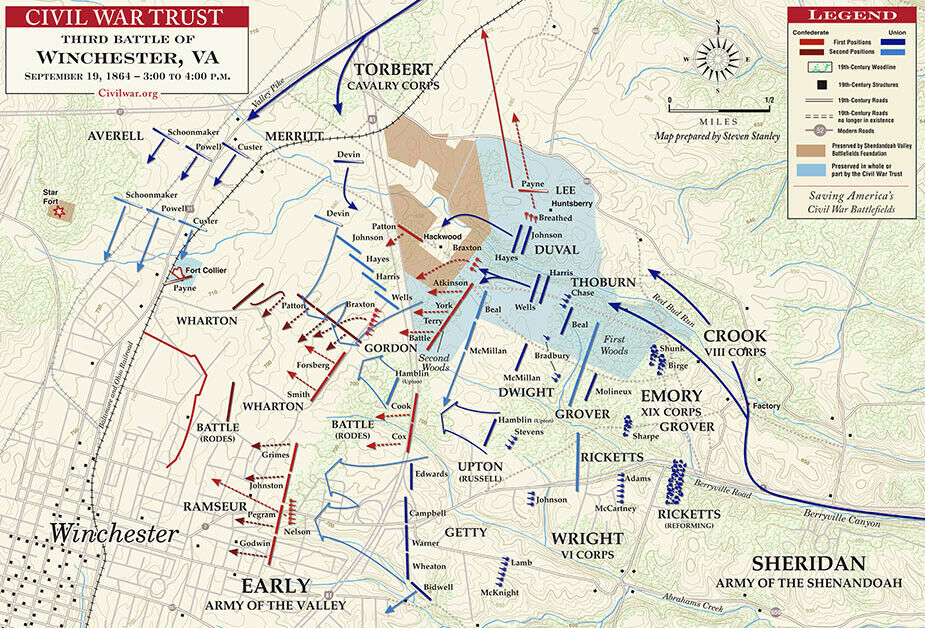

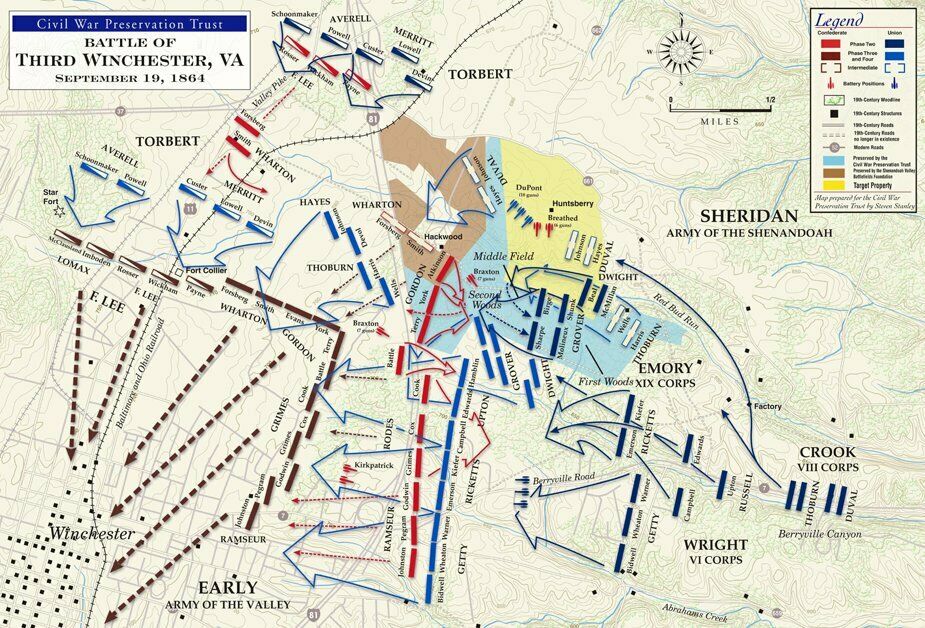

The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Opequon or Battle of Opequon Creek, was an American Civil War battle fought near Winchester, Virginia, on September 19, 1864. Union Army Major General Philip Sheridan defeated Confederate Army Lieutenant General Jubal Early in one of the largest, bloodiest, and most important battles in the Shenandoah Valley. Among the 5,000 Union casualties were one general killed and three wounded. The casualty rate for the Confederates was high: about 4,000 of 15,500. Two Confederate generals were killed and four were wounded. Participants in the battle included two future presidents of the United States, two future governors of Virginia, a former vice president of the United States, and a colonel whose grandson became a famous general in World War II.

After learning that a large Confederate force loaned to Early left the area, Sheridan attacked Confederate positions along Opequon Creek near Winchester, Virginia. Sheridan used one cavalry division and two infantry corps to attack from the east, and two divisions of cavalry to attack from the north. A third infantry corps, led by Brigadier General George Crook, was held in reserve. After difficult fighting where Early made good use of the region's terrain on the east side of Winchester, Crook attacked Early's left flank with his infantry. This, in combination with the success of Union cavalry north of town, drove the Confederates back toward Winchester. A final attack by Union infantry and cavalry from the north and east caused the Confederates to retreat south through the streets of Winchester.

Sustaining significant casualties and substantially outnumbered, Early retreated south on the Valley Pike to a more defendable position at Fisher's Hill. Sheridan considered Fisher's Hill to be a continuation of the September 19 battle, and followed Early up the pike where he defeated Early again. Both battles are part of Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley campaign that occurred in 1864 from August through October. After Sheridan's successes at Winchester and Fisher's Hill, Early's Army of the Valley suffered more defeats and was eliminated from the war in the Battle of Waynesboro, Virginia, on March 2, 1865.

The Third Battle of Winchester was the largest and costliest battle ever fought in the Shenandoah Valley. More than 54,000 men fought and over 8,600 became casualties in a ferocious see-saw struggle that saw the Confederates gradually forced back until a final decisive attack by Federal infantry and cavalry struck the Confederate left flank, breeching the defenders’ lines and sending the Confederates “whirling through Winchester.”

Thank you for viewing!